An anatomical and histological narrative of a subcutaneous muscle of the anterior abdominal of the anterior abdominal wall in human cadavers : A case report

Abstract

This report investigates a subcutaneous muscle layer found during routine dissections in four formalin embalmed human cadavers donated for medical training. The gross and microscopic morphology is described and potential implications in humans are raised. Tissue samples were taken from representative regions of the anterior abdominal wall and stained using Haematoxylin & Eosin followed by Masson’s Trichrome. The muscle tissue was seen in the deepest layers of the hypodermis of the anterior abdominal wall, with variable presentation between cadavers. Visually, it appeared as a thin greyish-pink or brown layer with variable morphology based on location, namely, sheet like, discontinuous, and enmeshed within fascial layers, with a thickness ranging from 1 to 5 mm. Tissue staining revealed muscle fibres in all samples. Our incidental findings add gross and histological evidence for the presence of a subcutaneous muscle layer found in the anterior abdominal wall of humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Experimental investigations of the human oesophagus: anisotropic properties of the embalmed muscular layer under large deformation

Article Open access27 April 2022

Constructing Detailed Subject-Specific Models of the Human Masseter

Chapter © 2017

Abdominal wall regenerative medicine for a large defect using tissue engineering: an experimental study

Article 30 July 2016

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, books and news in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.

1 Introduction

Traditionally, subcutaneous muscle (SM) layers present in mammals have been regarded to be the panniculus carnosus (PC), which has been largely accepted to be vestigial and rare in humans [1]. The PC is defined as a subcutaneous layer of striated muscle that is present under the dermis and the panniculus adiposus, covering the dorsal, lateral, and ventral sides of the trunk in most mammals [1]. In humans, muscles like the platysma, cranio-facial muscles, palmaris longus, palmaris brevis, and cremaster, are typically regarded as PC remnants, and also rare variants like the Langer’s axillary arch and sternalis [1, 2]. Some sources also list smooth muscles beneath the skin like the corrugator ani, areolar muscle, and dartos as PC remnants [3].

In addition to the muscles mentioned above, recent reports of subcutaneous muscle layers found in humans have been reported as the PC. A SM layer, located in the anterior abdominal wall has been independently described as the PC in two case reports [4, 5]. However, these studies lacked any histological confirmation. A PC layer was reported and validated microscopically in eight human cadaveric heels studied in one research investigation, that sought to determine the relationship between the presence of the PC in human heels and pressure ulcers in the foot [6].

The PC has risen to prominence in recent years with increasing evidence of its involvement in wound healing, stem cell research, vascular research, muscular research, pharmacological research, and regenerative medicine [1]. In the background of an increased interest and research into the anatomy and function of human fascia [7], the presence of a SM layer and its relationship to fascia may be relevant to scientists looking into related structures. Potentially, the presence of this layer could influence the pathogenesis and prognosis of abdominal wall hernias, as some reports have attributed improved wound healing in regions where SM layers are located [1, 6]. Considering these discoveries, we submit the following report of a SM layer found in the anterior abdominal wall of 4 human cadavers adhering to recommended reporting protocols [8], and examining the significance of this layer and its probable association with the PC.

2 Case presentation

2.1 Case 1

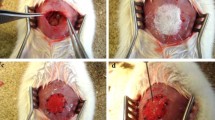

A greyish-pink fascia was discovered while dissecting the hypodermis in the abdominal region of an 81-year-old formalin-embalmed male cadaver that was dissected for post-graduate training in 2020. A distinct brownish layer was seen on both the left and right sides of the anterior abdominal wall. When efforts were made to tease the suspect layer in the loin, stringy fibres of muscle tissue became visible. Depending on its location, this suspect layer had varying morphologies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

a–c Photographs showing the SM layer in case 1 in incremental stages of dissection. a A transverse incision was made to create planes of separation between the Camper’s layer, Scarpa’s layer and the epimysium of the external oblique muscle. b The Scarpa’s layer was lifted, and the SM layer was seen lying on top of it. c Close-up of the SM fibres seen in the groin region. d, e, f Photographs showing the SM layer in cases 2, 3 & 4 respectively. White arrows, white arrow heads- SM layer; SM subcutaneous muscle

The muscle fibres were transversely oriented in the loin and appeared to blend laterally with the thoracolumbar fascia. Medially, these fibres thinned out and could not be traced to the midline above the umbilicus. However, below the umbilicus, the fibres were attached to the linea alba. In the supra-pubic region, the fibres were vertically oriented, thickened and enmeshed with the fibrous septa in the superficial fascia. Inferior to the loin, the fibres in the flanks curved in an inferomedial direction to fuse with the dartos muscle.

In the anterior abdominal wall superior to the umbilicus, the fibres were seen deep to the Camper’s fascia. In the lower part inferior to the umbilicus, they were interposed between the Camper’s and Scarpa's fascia. The layer was thicker in the flank and groin region and measured approximately four to five millimetres in thickness. The epimysium covering the external oblique muscles appeared intact and was present deep to the Scarpa’s fascia. The possibility of interpreting the muscular slips of the external oblique muscle as the SM layer was eliminated due to the fibre orientations and variable morphology of the SM layer, and the intact epimysium of the external oblique muscle.

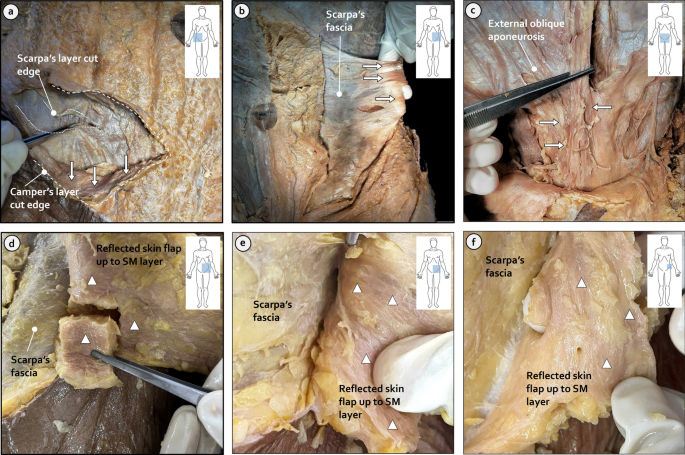

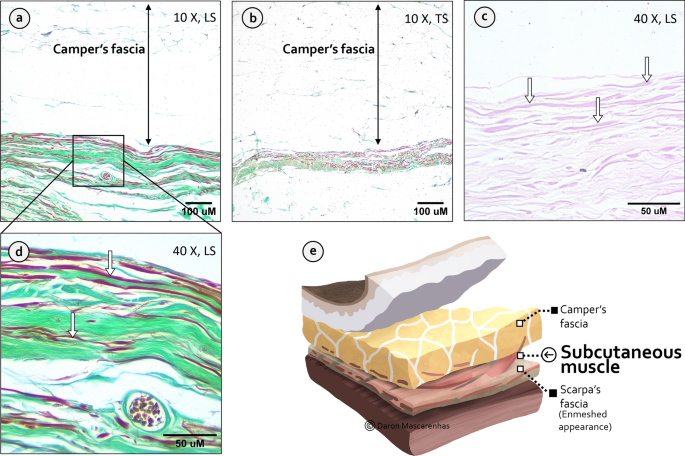

Two tissue samples of the superficial fascia of the anterior abdominal wall, one, from the lateral aspect (two sq. inch, three cm above the ASIS on left side) and two, from the supra-pubic region (one sq. inch, three cm above the pubic symphysis) were obtained for histological analysis. Transverse and longitudinal sections measuring 5 microns in thickness were taken after tissue processing. The sections were stained with Haematoxylin & Eosin. Cellular morphology was poorly visualized, and no nuclei were seen. Numerous structures staining darkly with eosin were seen arranged in linear arrays in longitudinal sections and as stippled dots in transverse sections, contrasting the light pink staining collagen fibres from the surrounding connective tissue. The sections were later stained with Masson’s Trichrome. All sections showed the presence of a diffuse layer of red stained fibres as similar to the preliminary staining, mostly interposed between the Camper’s and Scarpa’s fascia which stained green (Fig. 2). These structures appeared like thick fibres, consistent in size, exhibiting morphology similar to muscle fibres. Some cells, mostly fibroblasts exhibited pink staining cytoplasm. There was evidence of autolysis, and therefore the striations and other histological features were not visible.

Fig. 2

a, b, d Photomicrographs of the SM layer stained using Masson’s Trichrome. c Photomicrograph of the SM layer stained using Haematoxylin & Eosin. e Illustration showing the presence of the SM layer in the anterior abdominal wall (source: created by the author Daron Mascarenhas). White arrows- SM fibres; LS longitudinal section, TS transverse section

2.2 Cases 2, 3 & 4

A total of three formalin-embalmed human cadavers (68 to 85 years, male-two, female-one) dissected for undergraduate medical training in the same year were considered. Similar findings as noted in case 1 were observed when the students were dissecting the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 1d, e, f). The findings were incidental, as we had assumed that our earlier report was a rare variant. The superior and inferior extensions could not be determined as the thoracic region and parts of the hypodermis in the anterior abdominal wall were removed during student dissection. Tissue sections were obtained from all three cadavers from the lateral aspect of the anterior abdominal wall (two sq. inch, three cm above the ASIS on left side) that were undisturbed by the undergraduate dissections. The same staining protocol used in the first case was repeated, and the results were similar to case 1. Tissue autolysis precluded further examination of detailed cellular morphology.

3 Discussion

The prevalent view with regards to SM layers present in humans, is to associate it with the PC, which is considered to be vestigial and rare in humans. The PC in some mammals is said to be made up of striated fast twitch muscle fibres present in the ventral, dorsal and lateral aspects of the trunk with variable function that is species specific [1]. The function of the muscle is to contract involuntarily in the presence of an external noxious stimulus which leads to the contraction of the loose skin on the dorsal and lateral aspects of mammals [1]. The muscle varies in extent and thickness, with some mammals presenting a PC that is only a few cell layers thick to well-developed thick muscular coats [1].

The presence of a SM layer in the anterior abdominal wall of four human cadavers appears to challenge several contemporary evolutionary, developmental, and anatomical views. Before the discussion proceeds, some considerations are required to be borne in mind to interpret the findings of this report. Firstly, the PC in mammals is regarded by various sources to be made up of striated fibres [1], while some sources also include smooth muscles [3]. In our report, elucidating the fibre type was not possible due to autolysis. Further studies with fresh biopsies are required for robust reporting. Secondly, recent and evolving advances in fascial research has contributed to a renewed understanding of the structural and functional aspects of the hypodermis, prompting a reappraisal of its anatomy. Some authors have theorised that the PC is a modification of the hypodermis [9]. Mice model studies have revealed that the PC arises from dermomyotomal cells that express Engrailed-1. These cells which further express PAX3, PAX7 and MYF5 develop into the striated PC that is classically described as truncal muscular coats in mammals [1]. A possible mechanism for a SM layer being present in humans could be due to developmental arrest, delayed development or evolutionary reversion [10]. However, no studies investigating the developmental aspects of known subcutaneous muscles in humans exist. The criteria employed up to this point for attributing SM layers in humans as the PC hinge on morphological phylogeny. Given this, such a connection should not be regarded as definitive; therefore, we present our findings as a SM layer.

Two reports [4, 5] have documented the presence of a SM layer in the anterior abdominal wall as the PC but lack histological confirmation. The present report is the first to confirm the histological presence of a SM layer in the anterior abdominal wall. Case 1 did not merit further investigation due to prevalent views regarding the rarity of SM layers in humans and its association with the PC. When similar incidental findings were noted in our routine academic dissections (cases 2, 3, & 4), the evidence was compelling to re-examine this view. The authors would like to highlight two issues which might contribute towards missing this layer in cadaveric dissections. Firstly, due to academic heuristics of characterizing fascial tissue as indefinite, routine dissection practices remove fascia focusing only on well-described structures [7]. Secondly, variable morphology of this layer as noted in our findings might make it difficult to recognise it during dissection, especially when the muscle fibres blend or enmesh with the fascial anatomy.

Although the clinical significance of the SM layer in humans remains unexplored, implications from animal studies of the PC in pathological states show great promise. Mouse model experiments have demonstrated improved wound healing outcomes due to the regenerative capabilities of the PC layer [1, 6]. Therefore, the presence of the SM could theoretically serve as a potential prognostic factor for wound healing in abdominal wall surgeries, warranting further research. The PC is considered a valuable source for stem cell harvesting, and its role in muscular dystrophies has been the subject of recent research [1]. Similarly, the SM layer could be investigated as a potential site for stem cell harvesting in humans.

4 Conclusion

The findings from this report are strongly suggestive of a SM layer in the anterior abdominal wall of humans. Its variable appearance necessitates histological confirmation. However, it is difficult to determine if this layer is phylogenetically similar to the PC found in other mammals or if it is a layer of unknown significance; mostly due to paucity of reports, variable characterization of subcutaneous muscles in humans that have been conflated with the PC on the basis of morphological phylogeny, and lack of molecular studies tracing the development of this layer in humans and other mammals. As there is mounting research that has established the implications of the PC in various physiological and pathological states, it may be useful for anatomists, clinicians, radiologists, and surgeons to re-examine well established paradigms of the anterior abdominal wall anatomy. Further studies would be required to ascertain the fibre type, innervation, physiological function, imaging characteristics, and pathological implications of this layer in humans.

Daron Mascarenhas, V. Sumitra & Nachiket Shankar

Daron Mascarenhas, V. Sumitra & Nachiket Shankar